In an office environment, most people spend hours in a seated position in front of a computer screen. Repetitive activities, such as typing for long periods of time in a slouched position, may negatively impact posture and mobility, potentially leading to pain. One approach for improving back health and reducing the discomfort associated with repetitive workplace activities is to promote mobility, muscular balance and strength for optimal movement, posture and wellness.

The following five exercises can be easily incorporated into your workday, require little time and target common problems seen in the workplace. Get up and start moving!

Scapular Wall-Slides for Back, Shoulder and Neck Pain

Recommendation: 1-3 sets of 10 repetitions, twice per day

Starting position: Stand with your feet hip-to-shoulder width apart in a quarter squat while pressing your back and head flat against a wall. Attempt to place the arms against (or as close to as possible on) the wall at a 90-degree angle while keeping the back against the wall.

Upward phase: While maintaining the starting position, actively slide the arms directly up the wall without shrugging.

Downward phase: While maintaining the starting position, actively slide the arms directly down the wall to the arm starting position, without shrugging the shoulders. Tuck your chin while maintaining your head on the wall to prevent shrugging. This movement should be felt in the middle of the back.

Half-kneeling Hip-flexor Stretch

Recommendation: One set of 30 seconds to two minutes on each leg, three times per day

Starting position: Place the left knee down (on a pad) at a 90-degree angle, directly underneath the left hip and shoulder. Step forward with the left foot and position the knee at 90-degree angle. Place the hands on the hips or continue to perform work tasks, such as typing.

Static phase: Actively squeeze the right glutes to create a static contraction and hold it for up to two minutes without arching the lower back.

Release phase: Stop contracting and release. This stretch should be felt in the right hip flexors (the anterior segment of the right leg). Repeat the stretch on the opposite leg

Lacrosse Ball Myofascial Release of the Forearms for Hand, Wrist, and Elbow Pain

Recommendation: 1-2 sets of 30 seconds on each forearm, twice per day

Starting position: While seated, reach one arm in front of you with the palm up. Place a lacrosse ball on the desk underneath the arm, directly below the elbow.

Upward and downward phases: While applying tolerable pressure, slowly roll the ball upward and downward along the forearm extensors in a slow-paced fashion. Make sure to roll out the entire length of the forearm before concentrating on the area(s) that appear to be the most sensitive. Repeat on the other arm.

External Rotation of the Shoulder

Recommendation: 1-3 sets of 10 repetitions, twice per day

Starting position: Stand with feet hip-to-shoulder width apart. Bring the elbows against the sides of the body with the arms at a 90-degree angle.

Concentric phase: Slowly externally rotate both shoulders, while maintaining contact of the elbows with the sides of the body and squeezing the shoulder blades toward each other and slightly down.

Eccentric phase: Return to the starting position with control.

Banded (Seated) Hip Abduction

Recommendation: 1-3 sets of 10-15 repetitions, twice per day

Starting position: While seated upright, place the feet on the floor, hip-width apart, and place a mini band around the knees and the hands on the sides of the chair.

Concentric phase: Push both knees outward (as if you’re trying to break the mini band), while keeping your feet on the floor.

Eccentric phase: Allow the knees to return to the starting position with control, keeping tension on the band the entire time.

Remember, whether you’re in the office or at home, get up and move often! Use these strategies throughout the workday to improve posture and mobility, while decreasing the discomfort associated with sitting.

AUTHOR

Matthew Cain

Contributor

Matthew Cain is an Assistant Professor of Exercise Science at San Diego Miramar College. He is currently working towards his PhD in Exercise Science – Health and Human Performance at Concordia University Chicago. Matthew has a MS in Exercise Science and Sports Management from California Baptist University. Prior to San Diego Miramar College, Matthew was a full-time faculty member at CSUDH in the Department of Kinesiology and an adjunct professor at El Camino College. He has been published in the Strength and Conditioning Journal, International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy, and Journal of Canadian Chiropractic Association. He is an ACE Fitness Nutrition Specialist.

READ MORE

Get in the Know

Stay connected with us to get the latest health and fitness news, innovative workouts, healthy recipes and wellness tips.

Enter your email

Yes! I’d like to receive the latest news and updates from ACE.

SUBSCRIBE

search

TRENDING

What is cross training and why is it important?

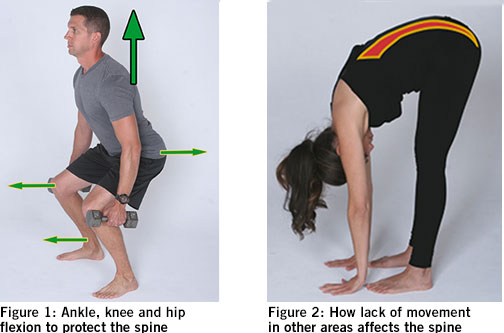

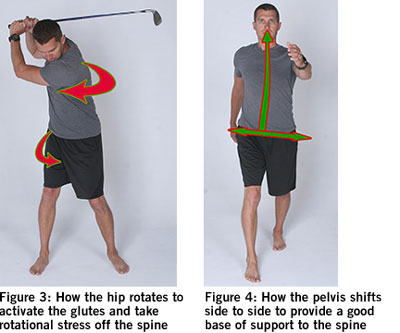

Is it ever okay for your knees to extend beyond your toes while doing squats or lunges?

How to Eat and Train for an Endomorph Body Type

Weight Training For Weight Loss

How to Use Blocks to Enhance Your Yoga Poses

ABOUT ACE

PROFESSIONALS

CERTIFICATIONS

RESOURCES

LEGAL

CONTACT US

Facebook

Twitter

Instagram

Pinterest

LinkedIn

Copyright© The American Council on Exercise. All Rights Reserved.

llwww.acefitness.org/education-and-resources/lifestyle/blog/7101/five-ways-to-improve-posture-and-mobility-at-the-office

Fat may seem like the enemy of civilized people—especially sedentary ones. Yet we cannot live without it.Fat plays a key role in the structure and flexibility of cell membranes, and it helps regulate the movement of substances through those membranes. Special types of fat, known as eicosanoids, send hormone-like signals that exert intricate control over many bodily systems, mostly those affecting inflammation or immune function.

Fat may seem like the enemy of civilized people—especially sedentary ones. Yet we cannot live without it.Fat plays a key role in the structure and flexibility of cell membranes, and it helps regulate the movement of substances through those membranes. Special types of fat, known as eicosanoids, send hormone-like signals that exert intricate control over many bodily systems, mostly those affecting inflammation or immune function.

Fat resides primarily in designated fat-storage cells called adipocytes. Most adipocytes are just under the skin (subcutaneous fat) and in regions surrounding (and protecting) vital organs (visceral fat). Nearly all fat in adipocytes exists in the form of triacylglycerols (TAGs or triglycerides). Each TAG consists of a backbone (glycerol) with three fatty-acid tails (see Figure 1).

Fat resides primarily in designated fat-storage cells called adipocytes. Most adipocytes are just under the skin (subcutaneous fat) and in regions surrounding (and protecting) vital organs (visceral fat). Nearly all fat in adipocytes exists in the form of triacylglycerols (TAGs or triglycerides). Each TAG consists of a backbone (glycerol) with three fatty-acid tails (see Figure 1). Fatty Acids in the Blood

Fatty Acids in the Blood At higher exercise intensities (>70% VO2max), total fat oxidation falls below the levels observed at moderate intensity (Horowitz & Klein 2000). This reduction in fatty-acid oxidation is coupled with an increase in carbohydrate breakdown to meet the energy demands of the exercise (Horowitz & Klein 2000).

At higher exercise intensities (>70% VO2max), total fat oxidation falls below the levels observed at moderate intensity (Horowitz & Klein 2000). This reduction in fatty-acid oxidation is coupled with an increase in carbohydrate breakdown to meet the energy demands of the exercise (Horowitz & Klein 2000).